Crafts

Since the Middle Ages, the village of Chiavari have been characterised by lively crafts and trade activities, which over the centuries have contributed to form the unique appearance of the city. New impetus for activities came from the Economic Society, founded in 1791, which promoted the Tigullio Exhibition, a showcase for local production activities.

Furniture makers and carvers

In the past centuries, the famous “bancalari”, worked the wood from the forests in the hinterland of Chiavari. Chiavari, together with Savona, stood as the most flourishing Ligurian timber market. The abundance of raw materials encouraged both the production of beech oars – “Via dei Remolari” (the oar-makers street) still exists in the old town -, and the production of wooden furnishings inspired by Genoese models, many of which can still be admired inside the sacred buildings in the area.

As far as civil furniture is concerned, it was probably the Genoese artisans who supplied the market. Joined in a corporation, they had already tried to establish a sort of protectionism since the 16th century, first requiring the members to reside in Genoa and subsequently establishing the possibility of enrolling in the Art for a fee with the obligation, for “foreigners”, to pay higher rates than the Genoese. The importation of products made outside the city was also prohibited. Therefore, the Chiavari cabinetmakers had to limit their production to artefacts inspired by Genoese models.

From the 16th century, the taste for carving spread, which is part of the great Ligurian tradition that began in the fifteenth century and culminated in the eighteenth with the experience of A.M. Maragliano.

In 1574, the Chiavarese Paolo Manfredi worked in the Collegiate Church of Pietrasanta. Another famous carver was Michelangelo Torriglia, who in 1632 built the choir of San Giovanni Battista Church, richly decorated, as well as that of San Giacomo di Rupinaro. The choir stalls of Nostra Signora dell’Orto (1738) from San Francesco Church are more sober and adapted in 1813 for the Cathedral by Giulio Descalzi, master of Giuseppe Gaetano Descalzi, “il Campanino”.

Chiavari chairs

The creation of Chiavari chairs dates back to 1807, the year in which the Marquis Stefano Rivarola brought some Parisian chairs to Chiavari and asked local artisans to copy them. Only one agreed to carry out the work. This was Giuseppe Gaetano Descalzi, son of a well-known cooper and nephew of the bell-ringer of the church of Bacezza, which is why he was nicknamed “Campanino” from the word bell in Italian.

He, elaborating on the Parisian model, created a new type of extremely light chair that was sturdy at the same time, characterised by a slender and rounded line, respecting the natural curvature of the wood.

The lightness was given by the use of maple wood (today cherry and beech are preferred); the strength derived from the assembly technique, obtained by fitting the components together and gluing them with a hot glue produced with animal bones. The seats were made directly on the chairs with the weaving of four strips of willow bark.

The “Campanino” chairs were very popular in the European courts of the 19th century, in Naples and in Moscow, in Turin and in Vienna and, from the 1930s onwards, they were exported all over the world. Antonio Canova also appreciated them for the combination of lightness and solidity.

At one time, the chair workshops were concentrated in the ancient quarter of Rupinaro. Over time, however they have depleted in number to the few companies represented in this exhibition.

Macramè

This typical production comes directly from the Arab world, with which the Ligurian sailors had relations in the Middle Ages. The name macramè derives from the Arabic word migraham which means fringe for embellishment.

At the end of the 15th century, the macramé workers merged with the Tovagliari, corporation, which had just begun in Liguria, and in the seventeenth century, macramé experienced its greatest diffusion. In the 18th century, it was still appreciated for embellishing household linen.

The work is complicated and involves knotting the threads of the towel fringes, using fingers only, without the aid of any tool.

In past centuries, Chiavari women used to work, in groups, under the arcades of the old town. The production was destined for export (especially to South America) and the House of Savoy really appreciated Chiavari’s macramé too.

Little by little, this craft has died out significantly too.

Bibliography

L’arte della sedia a Chiavari (chair art in Chiavari), exhibition catalogue, by L. Pessa-C. Montagni, Genoa 1985.

L’antica arte del macramè (the ancient art of macrame), by M.D. Lunghi-L. Pessa, Genoa 1987. M.D. Lunghi-L.

Pessa, Macramè. L’arte del pizzo a nodi nei paesi mediterranei (the art of lace knots in Mediterranean countries) Genoa 1996.

Famous people

Vincenzo Costaguta (1612-1660). His father Prospero had already occupied a prominent position in Rome as a senator of Rome, agent of the Republic of Genoa and governor of the Confraternity of San Giovanni Battista de’ Genovesi. In 1645, the Costagutas had been nominated marquises of Sipicciano and lords of Roccalvecce in the Viterbo area by the Pope. Vincenzo, a doctor in civil and canon law, moved from Chiavari to Rome at the time of the pontificate of Innocent X. Prothonotary apolistic, cardinal, he was secretary of the Apostolic Chamber. In December 1655, he hosted Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome, with whom he spent long hours discussing history, mathematics and music, subjects about which he was extremely knowledgeable.

Andrea Costaguta (1610-1670). A Carmelite friar and architect, in 1638 he was welcomed by the Duchess Cristina to the Savoy court, where he was appointed adviser and theologian to His Royal Highness. To him we owe the project of the Santa Teresa of the Discalced Carmelites complex and other works in the castles of Moncalieri and Valentino. Following a sinister event in his native Chiavari, in 1655 he was tried and sent to the convent of Sassoferrato.

Agostino Rivarola (1758-1842). Brother of the diplomat Stefano Rivarola, he was prothonotary apolistic at the conclave of Venice, in 1800, delegate to Perugia and Macerata, in 1808 he fell prisoner to the French because he remained faithful to the Pope. Governor of Rome, he was made cardinal in 1817 and since he was linked to Ravenna, he led the repression of the “seven carbonas”, which culminated in a trial where over 500 members were convicted in 1825. The following year he was the victim of an attack and back in Rome he was appointed head of the Water and Road systems.

Davide Vaccà (1518-1607). According to tradition, he was born into an ancient local family in the old town of Chiavari. With a doctorate in civil and canon law, he was a noted jurist and personal friend of Andrea Doria. He was Doge of Genoa from 1587 to 89.

Stefano Rivarola (1755-1827). Member of a noble Chiavari family, in 1783 he was ambassador of the Republic of Genoa to the Tsarina Catherine II, Empress of All the Russias. After returning to Chiavari and becoming governor of the city, he built a public oil lighting system based on the model of the one he saw in St. Petersburg. In 1790, the straight Caroggio streets were equipped with 19 lanterns and made Chiavari the first city to have public lighting. Founder and first president of the Economic Society.

Stefano Castagnola (1825-1891). A jurist, university professor, mayor of Genoa and minister, he was a leading figure in the Italian Risorgimento.

Alessandro Bixio (1808-1865). Older brother of the famous Nino, he grew up in Paris with his godfather, sub-prefect of the Department of the Apennines, and became fully involved in the political and cultural life of the city. He was editor of the Revue des Deux Mondes, the most important French magazine in the 19th century. As a deputy of the French parliament, he advocated armed intervention against the Roman Republic to help restore peace in Italy following the revolutions. Although he had conservative ideas, he was a fervent republican and when, in 1851, the coup d’état by Luigi Bonaparte opened the way to the Empire, he left politics devoting himself successfully to business and becoming an important financier.

Gerolamo “Nino” Bixio (1821-1873). Born in Genoa to a Chiavari family, he was a volunteer in the First War of Independence in 1848 and the following year he took part in the defence of the Roman Republic. After several years of travelling to South America, he returned to the command of a Battalion of the Alps battalion in 1859 and was among the organisers and leaders of the Expedition of the Thousand, beating the Bourbons from Calatafimi to the River Volturno. His strong character also made him the leading figure in the Bronte massacre, with which he wanted to punish the excesses to which the inhabitants had abandoned themselves upon the news of the arrival of Garibaldi. From 1861, he was deputy to the first Italian Parliament, where he showed particular expertise in the military and maritime sectors. Senator since 1870, he was alongside General Cadorna in the decisive attack for the conquest of Rome. He then resumed his passion for the sea at the command of a ship he had designed himself, which travelled with a mixed system of sail and steam, and it was on that ship that he died while sailing for Indonesia.

Michele Bancalari (1805-1864). Piarist father, he was a lecturer at the Nazarene College in Rome, then at Oneglia, Finale and Savona. In 1846, he became professor of Physics at the University of Genoa and at the same time was Provincial of the Order of Piarists. His name is linked to the discovery of the diamagnetism flame, which he presented at the IX Congress of Italian Scientists held in Venice in 1847. His theory was appreciated by the great physicist Michael Faraday, who used it as the basis of his own study on the magnetic behaviour of aeriform substances.

Giovanni Antonio Mongiardini (1760-1841). He graduated in Medicine at the University of Pisa in 1797. He supported the Jacobin ideas that led to the formation of the Ligurian Democratic Republic, in which he was part of the provisional government, the Police Committee and, in the subsequent Napoleonic period, the Chemical Section of the Imperial Academie. In Chiavari, he was city councillor and entered the Legislative Corps of the Department of the Apennines. France awarded him the Legion of Honour. Later, he continued teaching medicine in the University of Genoa, publishing numerous works.

Bernardino Turio (1779-1854). Born in Chiavari in a place called Rupinaro, he graduated in Pharmaceutical Chemistry in Genoa, and then dedicated himself to botany under the guidance of professor Domenico Viviani from Levanto. In 1806 the very young Bernardino, urged by professor Antonio Mongiardini, a chemist and naturalist from Chiavari, collected as many as 640 specimens of plants , from Sestri Levante, Rapallo, Val d’Aveto and Val di Vara and wrote a much-appreciated essay on them, which merited publication. In the city, he practised as a pharmacist, yet continued his naturalistic studies, which led him to study the marine algae of the Gulf of Tigullio. He abandoned the subject owing to financial problems. Later on, Giovanni Casaretto continued his studies.

Giovanni Casaretto (1810-1879). After graduating in Medicine, he made his first botanical observation in Odessa in 1836 together with the naturalist De Verneuil. During a subsequent trip around the world with the zoologist Caffer (1838), he had to take shelter in Brazil and while in Rio de Janeiro he conducted a thorough research project on the area that enabled him to collect a large number of botanical specimens – later given to the University of Genoa -, which he collected in the work Novarum Stirpium Brasiliensium Decades, printed in Genoa in the years 1842-45.

Federico Delpino (1833-1905). This great botanist was born into a modest Chiavari family. Due to his delicate constitution, he spent entire days in the open air in a small garden adjacent to his home (now belonging to the Economic Society). Here, he made his first observations on nature, especially the relationships between plants and insects. He began studying mathematics, but rediscovered his true vocation during a trip to the East, where he was able to study exotic flora. He thus resumed his botanical studies and, having moved to Florence, began to attend the Botanical Museum, the Orto dei Semplici and the Webbiana Library.

In 1865, his observations on the entomophilous fertilisation of the Arauya albens earned him entry into the academic world as an assistant to Professor Parlatore, director of the Botanical Institute of Florence. He then became professor at the University of Genoa, Bologna and, Naples, where he died. His writings are still the subject of in-depth studies. Particularly interesting is his correspondence with Darwin (kept at the Economic Society of Chiavari), in which Delpino – advocate of a rigorous scientific observation – was critical of Darwin’s pangenesis theory. The same English scientist wrote of him: “many writers have really criticised this hypothesis [pangenesis]; my best recollection is that of professor Federico Delpino entitled On the Darwinian Theory of Pangenesis (1869). Professor Delpino rejects the hypothesis I expressed, and I have profited greatly from the criticisms he made on this subject … ».

Diego Argiroffo (1738-1800). Franciscan friar, he was part of the circle of Chiavari intellectuals who animated the Economic Society. The aversion to Austria led to Father Diego’s death. Refusing to praise the Emperor, he was shot by the Austrians in 1800 on Monte Fasce, the first victim killed on Italian soil for political reasons. His manuscript work is well known. Historical and Chronological Memories of the City, State and Government of Genoa taken from several analysts and writers and authentic monuments,1794-1799, preserved at the University Library of Genoa.

Angelo Della Cella (1760-1837). He was born in Chiavari around 1760. Little is known about his life, but he certainly assimilated the Enlightenment ideas that spread to Chiavari at the end of the 18th century. He was buried in deconsecrated land. He embarked on the difficult work of the Memorie di Chiavari, preserved at the Library of the Economic Society and divided into three volumes. The second, entitled Chiavari’s Indigenous, Adventurous, Noble, Popular, Extinct and Existing Families, in which over six hundred local families are described, is a very useful tool for genealogical studies.

Carlo Garibaldi (1756-1823). A versatile and original intellectual figure, he was the most emblematic expression of the Chiavari Enlightenment. Born in 1756 in Prato di Pontori (today in the Municipality of Ne), he graduated in Medicine in Genoa in 1780, settling then in Chiavari, where he practised the profession and assiduously cultivated his interests in the historical and genealogical field, yet not neglecting his civil and political commitment. In April 1791, he was among the founders of the Economic Society, in which he held various positions, and took part in the creation of the Accademia dei Filomati, which promoted the organisation of a well-stocked public library. A strong Jacobin sympathiser, after the proclamation of the Ligurian Republic, he became part of the new Central Administration of Chiavari, which on his proposal renamed streets and squares with “revolutionary”-inspired names. The annexation of Liguria to the French Empire in 1805 marked his withdrawal from politics. The last part of his life was marked by bitterness and disappointment at the end of the revolutionary dream. Several historical and family-historical writings by Garibaldi remain, such as the Family Trees of Chiavari families, but his most famous work is the repertoire in three volumes “Of the Ancient and Modern Families of Genoa, extinct and living, noble and popular” preserved in the Library of the Economic Society. He is also responsible for some studies related to the Garibaldi family, preserved in the archives of the parish of Sant’Antonio di Pontori.

Enrico Millo di Casalgiate (1865-1930). His father, a prefect, inspired him to take up his military career. At the age of 14, he entered the Regia Marina, where he pursued a brilliant career. His fame is linked to the episode of the Dardanelles in the Italo-Turkish War. On 18 July 1912, as captain of the Millo vessel, driving five torpedo boats, he penetrated 15 miles of the Strait of Dardanelles controlled by Turkish enemies and obtained a gold medal for military valour.

The following year he was appointed Minister of the Navy of the Giolitti Government, a post he also held in the Salandra Government. He became governor in Dalmatia in 1918 and president of the Superior Council of the Navy from 1921 to 1923, leaving with the rank of admiral.

Nicola Giuseppe Dallorso (1876-1954). At the age of just fifteen, he began working for the Discount Bank of the Chiavari District, of which he became director at the age of 29, expanding the number of branches and turnover. In 1921, the bank was turned into the Bank of Chiavari and the Ligurian Riviera and was extraordinarily important in the Ligurian economy. Appointed Senator of the Kingdom in 1939, he was also awarded the knighthood of labour.

Umberto Vittorio Cavassa (1890-1972). Originally from Massa, he settled in Chiavari with his family in 1902. He was editor of the Roman newspaper Il Giornale d’Italia and in1928 began working for the Lavoro of Genoa, of which he became director in 1943. After the war, he was director of the Secolo Liberale (later Secolo XIX) until 1968. Cavassa is also known for his work as a narrator, which he began in the 1920s. His novels I giorni di Casimiro (1948) and Gente Diversa (1956) were set respectively in Chiavari and Sanremo in the late nineteenth century. La gloria che passò” (1961) is a historical novel that recalls the Liguria of the Napoleonic era.

Martino Ghio (1765-1842). At the end of the eighteenth century, Martino Ghio moved from the Sturla valley to Chiavari to open a “trading house” dealing in goods (oil, grains, agricultural products) to send to the large markets of Genoa and Marseille. A “bank fund” was subsequently opened, with the purpose of carrying out mainly foreign exchange transactions.

After the death of Ghio, the trading house “Fratelli Ghio fu Gio Batta ”(formerly “Fratelli Ghio fu Martino”) shut down and the Chiavarese family continued their banking activity with the establishment of “Banco Fratelli Ghio di G. B.”

In the decades between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the activity of the Bank, and Chiavarese financial institutions in general, developed considerably due to the growing exodus of the population towards the Americas: By anticipating the costs of expatriation, the institutions obtained the management of the emigrants’ remittances. In particular, the Banco prepared “travel cards” at a lower price than a normal ticket in exchange for compulsory work during the voyage.

Over time, the Bank gained the trust of the American population and the consulates present in Chiavari (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, United States, Uruguay, Venezuela). Thanks to these contacts and the trust acquired, the Ghio family became shareholders of Italian banks abroad, including the Banco de Italia y Rio de la Plata.

On 1 April 1934, Banca Commerciale Ligure, a limited company established in Genoa on 10 October 1925 as the “Piccolo Credito Ligure”, changed its corporate name to the Banco Ghio, also taking over the banking business of the Chiavarese family.

In 1970, the San Paolo Banking Institute of Turin endorsed the taking over of the residual assets and liabilities of Banco Ghio.

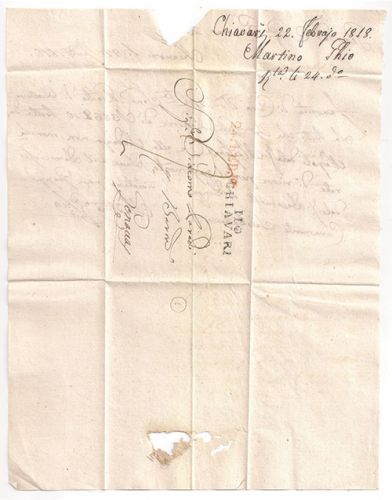

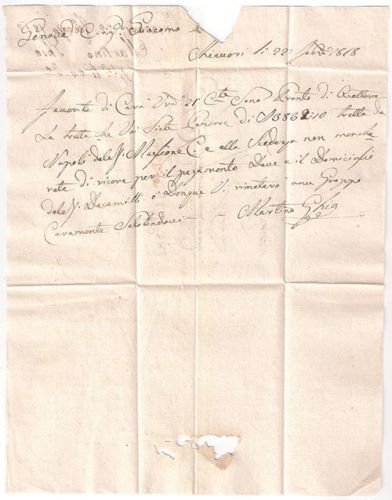

Letter from Martino Ghio: